The Nature of Money: Beyond the Illusion of Currency

Understanding the essential differences between money and currency, price and value, and how modern financial systems have transformed our understanding of wealth

In our modern world, understanding the basics of how things work has become surprisingly difficult. Complex layers of information, technical jargon, and specialized knowledge often obscure fundamental principles that should be simple to grasp.

This is particularly true in economics and finance. The global monetary system has evolved into such an intricate network that many of us have either given up trying to understand it or simply accept it as an automated, self-running machine. Financial experts often discuss markets and money from within the system, rarely stepping back to explain how it all works in plain language.

This essay intends to solve this challenge. It intends to go back to basic principles of the financial monetary system and break them down to their most simple values, void of complex jargon by which everyone can understand. By examining these foundations, we can better understand how the entire system works.

Let's begin with some fundamental questions:

When we want to measure the value of something, we usually compare it to the dollar, but when we want to measure the value of a dollar; if everything is pegged to the dollar, how can its true value be derived?

When you hold a $100 bill, what gives it value? After all, this bill is just paper printed with ink. What is the difference between monopoly money and banknotes printed by a central bank? What really gives them value? How is this thing measured?

In order to find the true answers, we need first to understand two principles:

The difference between money and currency.

The difference between value and price.

The Foundation of Exchange: From Barter to Basic Value

To understand the distinction between money and currency, we must first understand how humans developed systems of exchange and value.

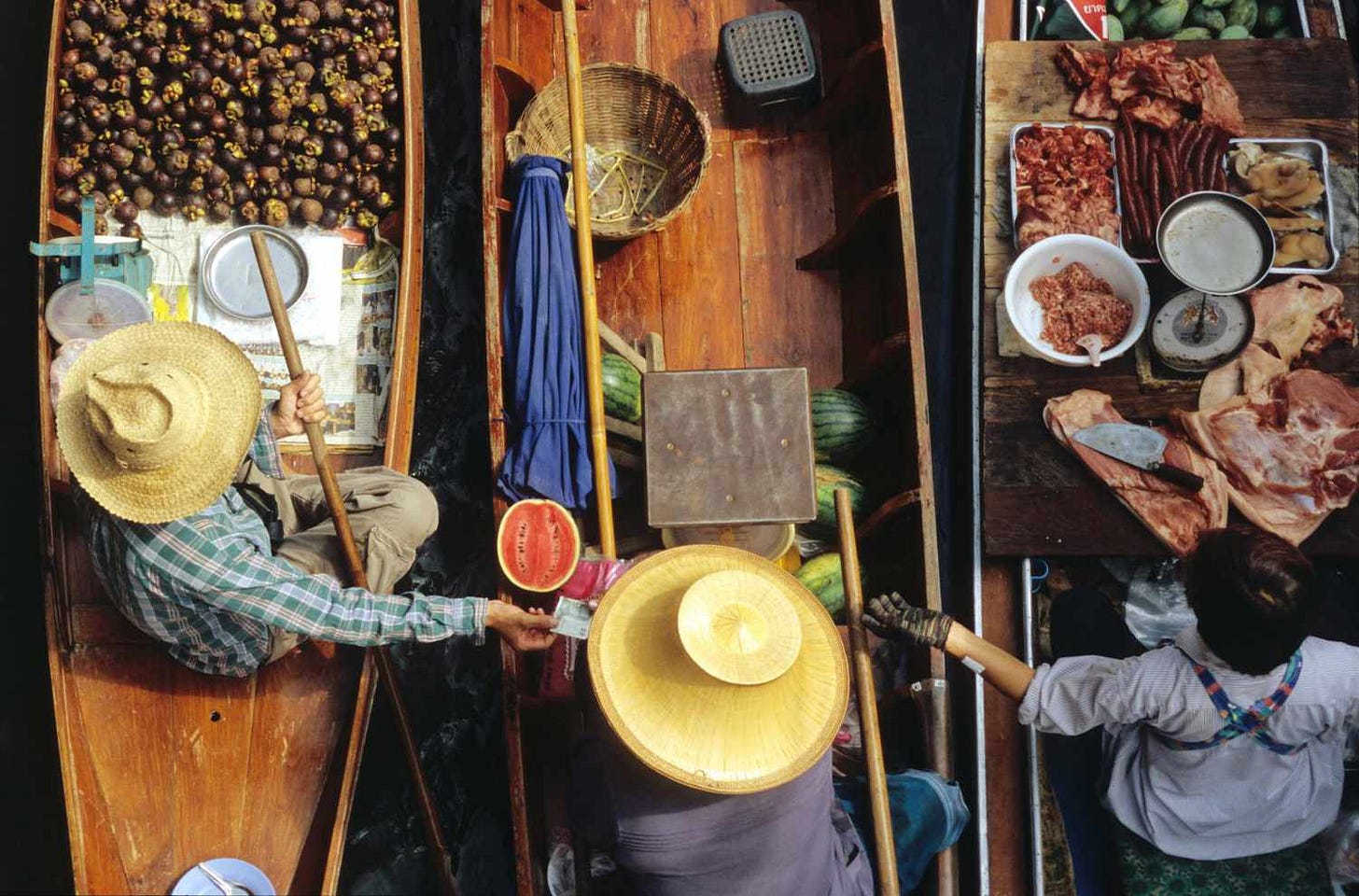

Thousands of years ago when the only thing that existed was barter, it seemed everything was simpler. If you were a fisherman who fished for a living and you wanted wild mushrooms or carrots or bread or whatever, what did you do? You exchanged the fruit of your labor with another.

The key question was: How was the trade calculated? How did they decide how many fish to give in exchange for wild mushrooms?

The fisherman thought to himself; "It took me such and such a time to invest energy (in the form of work) in order to yield output in the form of one fish." In the same way, the mushroom picker calculated how long it took her to invest energy for the yield of output in the form of one basket of wild mushrooms.

And so, at the time of the exchange, they reached an agreement about the measurement of the investment of work and time that yielded the same return, more or less. In our example, for instance, that one fish would be equivalent to a small basket of wild mushrooms.

What this shows us is that if we want to find some kind of basic underpinning - a basic measuring value - everything begins and ends with work. That is, the expenditure of energy required for activity is the basic value by which trade is measured.

This fundamental principle - that value derives from invested energy and time - remains constant regardless of how we represent it.

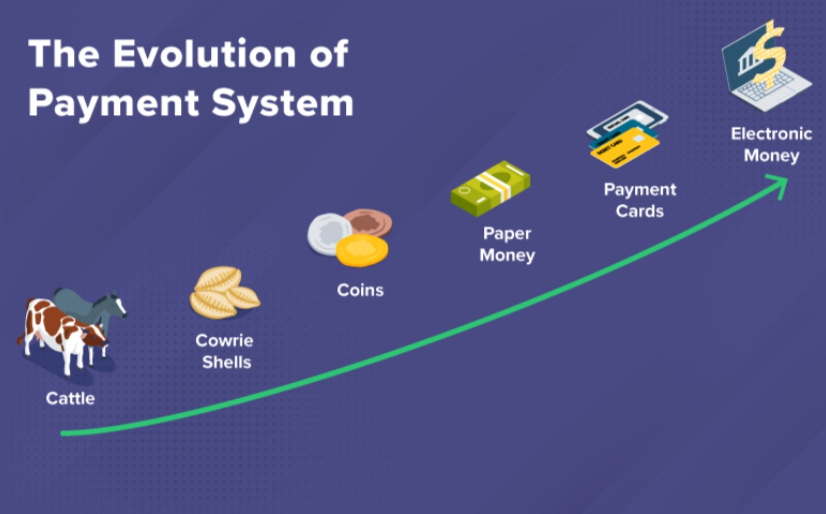

As societies grew more complex, they needed more efficient ways to represent this stored value of work. From the barter system, which dominated for thousands of years, societies experimented with various mediums of exchange: cattle, feathers, salt, shells, and gems, ultimately settling on precious metals like silver and gold. Each step made trade more efficient, but the underlying formula remained unchanged: the value represented still corresponded to human energy expended in work.

This brings us to the crucial distinction: Money is anything that stores the value of human work and enables exchange. Currency, on the other hand, is simply a token we use to represent that stored value. While all money can serve as currency, not all currency necessarily functions as true money - a distinction that becomes critical in understanding our modern financial system.

Our ancestors discovered that precious metals offered unique advantages as a medium of exchange. Their choice wasn't arbitrary - it was based on three essential properties that made precious metals ideal for storing and transferring value.

First, precious metals possess remarkable durability. They do not deteriorate, rust, or wear out over time. Second, their quantity is naturally limited - precious metals cannot be created out of nothing, as their formation requires geological and astronomical processes that take millions of years. Third, they are compact and portable, taking up relatively small space compared to goods, making them practical for trade.

The true breakthrough came with a profound realization: the amount of time and work required to search, find, filter, purify and prepare raw gold and silver and convert them into coins and bullion could be "engraved" as a formula on the medium itself. This standardization of value revolutionized trade.

Consider this practical example: a gold coin with a diameter of 1 inch represented the expenditure of energy equivalent to the work required for a fisherman to produce, let’s say, 80 fish. This standardization transformed commerce. Instead of transporting large quantities of goods for trade - imagine carrying enough fish to buy a house - people could now conduct significant transactions with a few precious metal coins in their pocket.

This innovation catalyzed economic development in several ways. Once we could embed a formula of energy expenditure into precious metal coins, we could convert energy into services and products more efficiently. This efficiency sparked a virtuous cycle: streamlined trade led to further developments, enabling us to manipulate materials in increasingly sophisticated ways and create new products.

Perhaps most importantly, the silver and gold coins maintained their value over time because the formula embedded in them remained constant. This stability stemmed from an unchanging reality: today, the same fundamental amount of energy is required to search, find, filter, purify and convert raw gold and silver into coins. This intrinsic connection between value and energy expenditure explains why precious metals have served as reliable stores of value for millennia.

This historical development helps us understand why true money must be both a store of value and a medium of exchange - qualities that made precious metals so effective and that modern currencies sometimes struggle to maintain.

The Rise of Paper Money: The Innovation of Promissory Notes

As trade expanded and wealth accumulated in medieval Europe, a new challenge emerged: the practical difficulties of transporting and securing large amounts of precious metals. This problem sparked one of history's most important financial innovations.

Merchants and goldsmiths, who would later become the first bankers, proposed an elegant solution to their customers: "Why are you carrying coins and gold bars with you? Deposit them in a safe place (a bank) and in return we will give you a claim check for the total value of those metals you deposited."

To understand this revolutionary concept, consider a familiar modern parallel: when we deposit clothes at the dry cleaners, we receive a paper receipt - a claim check. This claim check serves as a voucher, proving our ownership of the clothes in the cleaner's possession. In much the same way, the first paper money represented claims on precious metals stored in secure vaults.

These paper claims became known as IOUs - a simple abbreviation for "I Owe You." Each IOU instructed the bank that you were the owner of specific capital deposited in their vault, equal to the amount written on the note. For example, if you had an IOU note that said $200 on it, it meant there was gold bullion or gold/silver coins of equivalent value in the bank's safe belonging to you.

This innovation transformed commerce in several crucial ways. First, it eliminated the risks and inefficiencies of transporting precious metals, particularly for large transactions. Second, these promissory notes provided a form of insurance - if you lost the paper claim, you hadn't lost the actual metals stored in the vault, which constituted the real value. Finally, it introduced a new level of flexibility into the monetary system, as these claims could be transferred between parties more easily than physical metals.

However, this development also marked a crucial distinction in monetary history: for the first time, the symbol of value (the paper note) became separated from the actual store of value (the precious metals). This separation would later prove significant in the evolution of modern currency systems.

The Evolution of Banking: The Innovation of Credit

As commerce expanded and economies grew more complex, the simple system of promissory notes backed by precious metals began to show its limitations. Economic growth was constrained by the physical supply of gold and silver, leading bankers to consider a revolutionary idea:

"What would happen if we loaned people claim checks beyond the amount of gold bullion that is in the bank vaults?"

This seemingly simple question led to one of the most transformative innovations in economic history: the creation of credit. At its core, credit is a formula that calculates and converts future work into present value, plus interest. This innovation effectively allowed future productivity to be borrowed against and used in the present.

The addition of interest served two crucial purposes for banks. First, it provided income for banks as businesses that needed to sustain their operations. Second, it compensated banks for the risk they took in creating credit beyond their physical gold reserves. This risk was real - if too many customers demanded their gold at once (a "bank run"), the bank would be unable to meet its obligations.

To manage these risks, banks developed sophisticated systems and principles. Economists and bankers created intricate formulas to determine safe lending thresholds that would maintain economic stability. The key was maintaining a careful balance: loans could expand the money supply beyond the physical precious metals in bank vaults, but only up to a certain point. Most promissory notes still needed to be backed by physical silver and gold to maintain confidence in the system.

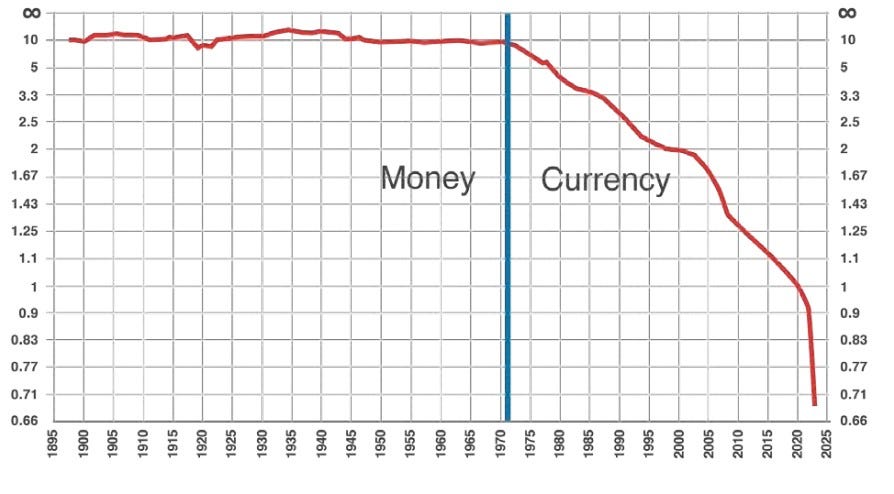

This delicate balance between credit expansion and physical backing worked relatively well for decades. However, the system faced its ultimate test in 1971, when U.S. President Richard Nixon ended the Bretton Woods monetary system. With this historic decision, the financial system was officially disconnected from the gold standard, ushering in a new era of FIAT currency economy.

This transformation marked a fundamental shift in how money functioned - from a system based on physical precious metals to one based primarily on trust and government authority.

Until 1971, the global financial system operated on a fundamental principle: the entire world economy was based on precious metals backing up the vast majority of promissory notes in circulation. Each paper note represented a claim on real gold and silver, plus a tangible amount of credit calculated from future gross national product.

The 1971 shift to a purely credit-based economy marked a revolutionary change. The traditional restraints were removed, allowing IOUs to be printed without the limitations previously imposed by physical precious metal reserves. As time passed, this new freedom led to increasingly aggressive monetary expansion.

The digital revolution amplified this transformation. When technology came along, credit or debt (they are synonyms) became a tradeable currency in itself. Modern banking created an unprecedented situation: the ability to create currency through simple computer entries. Unlike traditional banking, where each note represented physical wealth or future production, this new credit is not backed by any tangible assets.

To understand the profound nature of this change, consider this analogy: Imagine standing in line at the grocery store, and when it's time to pay, you simply take out a pencil and a blank piece of paper, scribble "100 dollars" and hand it to the cashier who receives it. While seemingly absurd, this parallels how our current financial system operates. If we return to our original example of the fisherman and mushroom merchant, modern currency represents a similar abstraction - exchanging essentially created numbers for real goods and labor.

This transformation highlights a crucial disconnect in our modern monetary system. While it's true that energy is required to convert raw materials into paper currency or maintain digital banking systems, there's a fundamental imbalance: the energy value these notes represent bears no relation to the energy required to create them. This disconnect between creation cost and represented value marks a historic departure from traditional forms of money, where the medium itself required significant energy to produce and maintain.

This fundamental change in how money functions has profound implications for how we understand value, wealth, and economic stability in the modern world.

Our modern financial system rests on a remarkable premise: it all works solely on creating debt out of thin air. Rather than trading in instruments that store real value, we exchange claim checks that don't honestly represent stored energy or work.

This system operates at every level of the economy. Countries trade with each other on credit, creating currency based on future gross national product and/or future taxation. This isn't limited to government finance - all banks, whether central or commercial, don't lend existing resources but instead create new numbers and lend them with interest.

To understand this crucial point, consider a fundamental question: What's backing up the IOUs in your account? What gives them value?

The answer reveals the true nature of modern currency: The hours you must work in the future to make the payments on your mortgage or car loan. Your future labor has become collateral. Your house or car guarantees the value of those IOUs - if you stop making payments, the bank will take them. More importantly, it ensures you will work in the future to satisfy their IOU. This reveals a crucial truth: the only thing that gives any national fiat currency value is the exhaustion of future working hours from you.

This system creates a profound intergenerational obligation. The future enslavement of humanity is in direct proportion to the creation of debt in the present. Each new loan effectively mortgages the future of coming generations.

Consider the common example of a mortgage: In simple terms, a mortgage is a loan - promissory notes created by the bank - that converts your future energy investment (typically over 30 years) into present value. Essentially, it represents the amount of work you'll need to invest to produce the equivalent energy required to build the house, had you built it yourself.

This transformation of our monetary system has had a crucial consequence: since moving to a fiat economy that creates and trades debt without precious metal backing, we've steadily diluted the purchasing power of currency over time.

This brings us to our fundamental distinction: money maintains its value over time, while currency loses its value over time. This difference isn't just academic - it represents the gap between a system based on real stored value and one based on future obligations.

Understanding True Wealth: The Difference Between Value and Price

In our modern financial world, we often confuse two distinct concepts: Price means nothing. Value is everything.

While this statement might seem counterintuitive in a world obsessed with price tags, it reveals a fundamental truth about wealth and economics. Although the price of something may go up, its value can go down at the same time. This paradox lies at the heart of understanding true wealth.

Let's clarify these terms: Price is simply a measure we use to agree on how many units of currency will exchange a product, service, or asset. But value is measured by what can be bought with the proceeds once it is sold. This crucial distinction becomes clear through an example: if an investment doubles in price, but the cost of living (groceries, fuel, etc.) has increased 4 times during the same period, then despite the price increase, its value has actually halved.

Let's assume that over a 20-year period, your home has doubled in price. The natural assumption would be that you've doubled your wealth, but have you really?

The answer requires us to think in terms of relative value, not absolute prices. If you measure it against other real estate, the answer is no - selling your house won't enable you to buy two similar houses with the proceeds. You can only buy one. In this case, even though its price has doubled, its real value, measured against similar real estate, remains unchanged.

The picture becomes even more interesting when we compare across different assets. If the stock market has quadrupled during that same period, your house - despite doubling in price - has actually lost half its value when measured against stocks. This reveals an important strategy for preserving and growing wealth: if you had sold your house at the beginning of that 20-year period and bought stocks, you could later sell those stocks and buy two houses. This represents a 100% gain in real wealth, achieved by understanding the difference between price and value.

This example illustrates a crucial lesson: the apparent increases in your home's price were merely an illusion created by a currency losing its purchasing power. What appeared to be appreciation was actually just inflation in disguise, or alternatively, the debasement rate of the currency. This distinction between real appreciation and currency debasement is crucial for understanding true wealth creation.

This understanding of value versus price becomes increasingly important in our modern economy, where rapid currency creation can mask true changes in wealth and purchasing power.

Measuring Real Value: Putting Theory into Practice

After understanding the fundamental differences between money and currency, and between price and value, we can now address a crucial question: How do we measure true value in a world of changing currencies?

The challenge lies in finding a stable reference point. We begin to see that the only way to measure the value of the dollar is by comparing it to something that retains the basic element it should preserve: work. Without such a benchmark, once the dollar or any other fiat currency becomes the object of measurement, we cannot accurately track changes in value over time.

This problem is similar to trying to measure sugar content by comparing a lemon tart to a chocolate cake by tasting each one. Since both are enriched with sugar, there is no reference point.

While precious metals traditionally serve as this reference point, we can demonstrate this principle using something more familiar: Campbell's tomato soup. This example, popularized by Mike Maloney in his book "The Great Gold & Silver Rush of the 21st Century Rush," perfectly illustrates how everyday items can reveal profound economic truths.

The soup works as an ideal measure because its value is determined by the amount of work required to convert raw materials into a final product. This principle can apply to anything that retains value over time: wood, Formica, coffee - whatever product requires a consistent amount of work to produce.

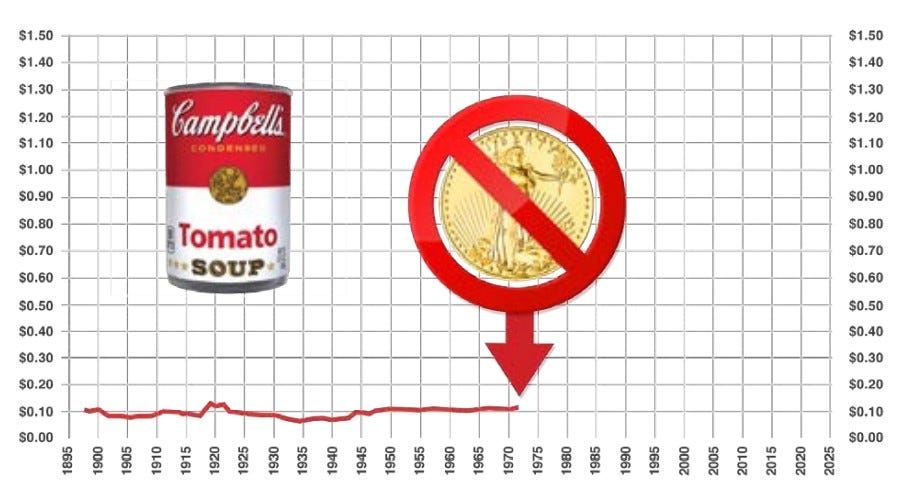

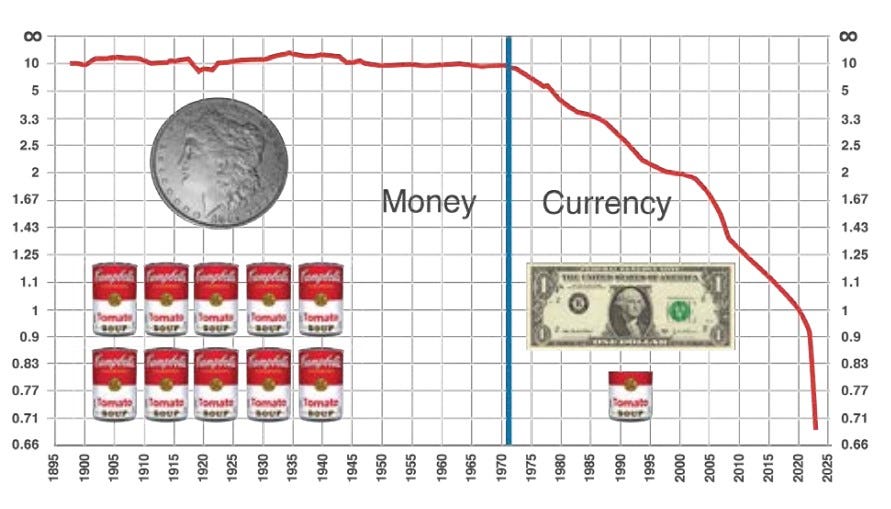

Looking at the historical price charts, we can see a striking pattern. From 1898 to 1971, the price of Campbell's soup remained remarkably stable. The critical moment came in 1971, when we severed our connection with money (gold) and switched to fiat currency only. After this point, the price began an unprecedented climb.

But here's the crucial insight: it wasn't the soup that changed... it was the dollar. The can of soup didn't increase in value - the currency decreased in purchasing power. This becomes crystal clear when we measure the dollar in terms of soup.

The numbers tell a stark story: for 70 years, from 1898 to 1971, one dollar of real money could buy about 10 cans of Campbell's tomato soup. Today, one dollar of fiat currency buys only 2/3 of a can. This represents a 93% loss in purchasing power relative to the soup since 1971. While the price of soup is now almost 15 times higher than its average price of $.10 from the gold standard era, the change reflects currency debasement, not increased value.

This pattern has accelerated in recent years. The price increases occurring in the last two years aren't because products have increased in value, but rather reflect the rapid loss of purchasing power of the dollar, particularly following the unprecedented currency creation during Covid (when approximately 30-40% of the national debt was created through various stimulus plans).

This example perfectly illustrates our earlier theoretical points: the difference between money and currency isn't just academic - it has real, measurable effects on purchasing power and wealth preservation.

Conclusion: The Circular Nature of Modern Currency - And Its Hidden Costs

Our modern financial system reveals a profound irony in which we’re caught in a financial system where we're essentially trading promises of future labor for present consumption.

The implications of this system are staggering: Today, in our purely fiat-based economy, we have begun to trade future work hours for an illusion of growth and economic freedom in the present. The burden of this system becomes clear when we consider that every child born today in the U.S., before taking their first breath, inherits an invisible price tag of $150,000 - representing the work hours they must contribute to repay accumulated national debt.

This system has led us to forget a fundamental truth about wealth: True wealth stems from work generated each day by human beings themselves. A copper pipe doesn't emerge from the ground in its final form, nor does diesel fuel. Between raw material and finished product, energy - in the form of work - must be invested. This energy is action potential, stored and replenished within the human body daily, designed to be released towards productive activity.

Consider our economic origins: Before currency, we had the barter system, where the expenditure of energy towards an activity was the basic unit of measurement. The energy required to catch one fish would be equivalent to that needed to pick a small basket of wild mushrooms. While we've sophisticated this system over centuries, the fundamental formula remains unchanged.

Yet our complex monetary system has obscured this basic truth: everything begins and ends with individual human energy. Gold, while valuable, is merely a store of value - it requires human interaction to be meaningful. The reservoirs of energy within each person represent true wealth, an innate state that can never be separated from the individual. The tragedy of our modern system is that it has led to a form of collective forgetting - where we've lost sight of this fundamental relationship between human energy and value.

This understanding reveals a profound truth: true wealth lies in recognizing our inherent capacity for productive work, while slavery - whether physical or financial - stems from forgetting this essential connection. Our modern financial system, built on circular logic and future debt, represents perhaps the most sophisticated form of this forgetting.

To bring the most important point home, I’d like to quote an excerpt from Joshua Maree’s book, Debt by Design:

Readers are encouraged to stop for a minute and contemplate the circular reasoning that underpins our debt-based monetary system.

The public believe that deposits have value.

The value of the deposits is determined by the value of the loans.

The value of the loans is determined by the ability of the public to repay their debt.

And there you have the circular argument. Looking at the reasoning in reverse; the ability of the public to repay their debt determines the value of the loans, and the value of the loans determines the value of the deposits. Consequently, if the public ever tried to determine what it is that instils value into their deposits, they would end up staring into a mirror.

This epiphany is uncomfortable and bewildering for many.