The Cellular Deception: Part I: Origins of the Germ Theory Paradigm

How a fragmented worldview shaped modern medicine and disconnected us from natural laws

Introduction

For over a century, Germ Theory has stood as the unchallenged foundation of modern medicine, shaping our understanding of disease, health, and the human body. So deeply embedded is this paradigm that most of us have never considered examining its premises—we simply accept that microscopic invaders cause disease, and our bodies are battlegrounds where these wars are waged.

This series invites you to step back and examine this foundational paradigm with fresh eyes. Rather than beginning with the assumption that Germ Theory is correct, we'll trace its historical development, examine the consciousness shift that accompanied it, and explore the profound consequences of adopting this mechanistic view of life.

In this first installment, we journey back to the origins of Germ Theory, not merely as a scientific model but as a reflection of a fundamental shift in human consciousness—a shift away from holistic understanding toward fragmentation and mechanization. We'll see how this paradigm arose not simply from scientific discovery but from broader cultural, economic, and psychological forces that transformed how we perceive ourselves and our relationship with the natural world.

Our exploration begins with a simple question: What if our most basic assumptions about disease and health have been fundamentally misaligned with nature's processes? And what might we discover when we allow ourselves to question what has long been presented as unquestionable truth?

The Source of Confusion: How the Intellect Perceives Reality

Germ theory stems directly from how the human intellect interprets observable phenomena.

Humans are unique as the first species with self-reflected consciousness – mental awareness. This new cognitive framework divides reality into relative relationships between an observer and observed phenomena. The mind operates by juxtaposition; creating opposites to generate knowledge. We cannot comprehend something without contrasting it with its opposite. These extremes establish our measurement spectrum.

This framework categorizes our observed world into binary divisions like 'good' and 'bad' or 'this' and 'that' – classifications that constantly shift according to perspective. Heat becomes "good" when warming a winter home but "bad" when stranded in the Gobi Desert without shade. A knife can kill but it can also both heal (or really be valuable in making a salad). But again, such conclusions never represent the fundamental reality – they remain perpetually relative.

The human intellect primarily processes reality through binocular vision, which provides our sense of depth. We confidently declare something "real" when we can see it, while conversely assume that what we don’t see doesn't exist. This materialistic approach fundamentally shapes our perception.

However, despite observing three-dimensional phenomena, our intellect struggles with analyzing information in this medium. Instead, by its very nature, it must translate these observations into two-dimensional formats through comparison and contrast.

As a result, our explanations typically follow "straight-line" reasoning—the shortest distance between two points. We even express these through our primary tools—paper, screens, diagrams—which translate three-dimensional information into two-dimensional formats (length × width) to accommodate our intellectual consciousness, as well as its limitation. For example, physicists represent the universe's age as a linear progression; geneticists arrange DNA nucleotides in sequential order. However, this dimensional compression causes the intellect to lose vast amounts of information during processing, as phenomena themselves are not two-dimensional.

The Mind's Measurement Paradox

The human mind operates in a two-dimensional medium while reality exists in multiple dimensions. Natural laws align with this multi-dimensionality. The universe, both macrocosmically and microcosmically, contains no truly straight lines—only continuous spiral movements without beginning or end. Any point can simultaneously function as both cause and effect—a reality that the mind cannot fully comprehend.

This perpetual motion creates a fundamental challenge: how can the mind perform precise measurements?

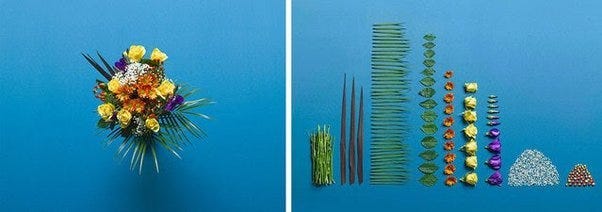

It cannot—unless it artificially freezes reality, deconstruct it into its smallest components, isolates them, and then juxtaposes these fragments to derive measurements and conclusions. The human mind fundamentally operates through separation. Its very mechanism requires breaking down every observed phenomenon into constituent particles to achieve understanding.

To use an analogy, modern science—as a product of rational analytical thinking—resembles a child throwing a toy truck against a wall. To understand the truck's nature and function, the mind must shatter it into individual pieces, examining each fragment separately. It cannot perceive the truck holistically, but only as disconnected parts that are smaller than their sum.

“He who breaks a thing to find out what it is, has left the path of wisdom."—J.R.R. Tolkien

These images perfectly illustrate our fundamental perceptual dilemma. What we perceive is not reality itself, but rather reality filtered through the lens of our mental measurement systems.

The gif above contrasts the geocentric and heliocentric models—two frameworks that appear visually similar yet represent radically different conceptual anchors. The mind naturally creates relative relationships based on whatever object becomes its focus. Once the Sun becomes the central reference point - i.e. the heliocentric model - celestial movements emerge in relation to it. When the focus shifts to the Earth as the center, an entirely different network of relationships emerges—though using the same visible data. Each focus point generates its own cascade of relative measurements, interpretations, and conclusions, like a unique pattern of falling dominoes. Yet both remain incomplete approximations.

This second gif reveals a more complex truth—the solar system's spiral movement through three dimensional space. Here we glimpse reality beyond our simplified models, where even the Sun, far from stationary, carves its own helical path through the cosmos. Yet even this visualization remains incomplete, in the sense that the sun’s trajectory is not a straight line. The Sun itself moves in a larger spiral toward the Milky Way's center, which in turn follows its own cosmic trajectory. Everything moves in a spiral. The same applies to the microcosm. Atoms and their “constituents” electrons move in a spiral fashion.

This layered reality exposes the mind's measurement problem: we cannot perceive without anchoring and without flattening to two-dimensional format. Yet every anchor we choose inevitably distorts. Our models are useful approximations rather than perfect representations. The difference between how we perceive reality and how reality actually exists isn't a matter of correction but of perspective—we can shift anchors and gain new insights, yet complete perception remains perpetually beyond intellectual grasp. That’s where wisdom comes to play. It’s only through wisdom that one can transcend the mind’s inherent limitation.

Body Consciousness

Conversely, biological systems operate more like parallel quantum processors, fundamentally different from the mental cognition.

Consider matter's quantum-mechanical nature: while atoms appear stable through our measurements, their core components – particularly electrons – exist as pure potential until observed. An electron doesn't occupy a fixed position but exists as a probability cloud until the act of measurement "collapses" it to a specific location.

This reveals a profound principle: Reality behaves differently when unobserved versus when subjected to our mental measurements. The "measurement problem" perfectly demonstrates the mind’s limitations – our very attempt to understand reality through observation fundamentally changes what we're trying to observe.

Hippocrates — the Greek whose name adorns the physicians' oath, which seems to have become lip service over the years — said: "The difference between medicine and poison is the dose."

In other words, from another angle, Hippocrates' insight reveals that the body's innate intelligence doesn't recognize the dualistic concepts of good versus bad that dominate our mental framework. This can be extended further: the body doesn't know what a bacterium, toxin, calorie, enzyme, protein, vitamin C, and so on are. Likewise, it doesn't understand what arthritis, flu, or cancer is. All these are byproducts of intellectual measurements.

At the same time, the belief that poison/medicine affects the body is incorrect. In reality, it's exactly the opposite. It is the body that acts on the medicine/poison, not the medicine/poison on the body. Although this claim may sound strange, it is nonetheless true.

There exists a regulatory system in the body that maintains its homeostasis. This system is the "vital force." This vital force works continuously, day and night, to preserve the body's health. The moment a harmful or unhealthy substance enters the body, the vital force springs into action and focuses on the task of eliminating the invasive material.

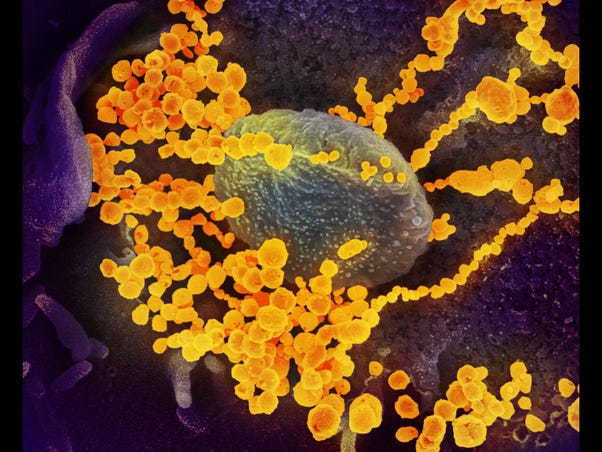

The Microscope's Revolutionary Impact

With the industrial era's dawn, we artificially expanded our vision through technological development. In science, the microscope represented a breakthrough that allowed our eyes to penetrate previously invisible realms.

The observing intellect suddenly gained "super vision," opening an entirely new world—like space travel in reverse, inward rather than outward. New forms and patterns emerged as we gained the ability to examine matter at its minutest levels. The intellect began decomposing and isolating observed materials into increasingly smaller components, leading to tremendous knowledge acquisition but also profound delusion.

Visually, the microscope created the illusion that we had reached matter's smallest level before emptiness—a singularity with no deeper level to explore. This apparent finality reinforced the intellect's fundamental mechanism: categorizing observed reality into linear cause-and-effect relationships defining every outcome.

Since we have remained fundamentally unaware of these intellectual cognition mechanisms—how the intellect fragments observations into discrete particles—this has led us to:

Inventing countless names for these separated particles, eventually losing sight of their interconnections through information overload.

Projecting the intellect's strategic traits onto observed microscopic particles, based on the outcome on the surface.

In other words, we have fallen into predictable traps when examining the microscopic world. Just as we positioned Earth or the Sun at the center, believing them to be the underlying representation of reality, we made the same mistake in the microscopic world, positioning germs at the center of our disease model.

We began attributing strategies and awareness to microscopic entities, categorizing them as "good" or "bad" based on surface observations. From then on, these relative observations transformed in our consciousness into absolute conclusions.

The Medical Misinterpretation

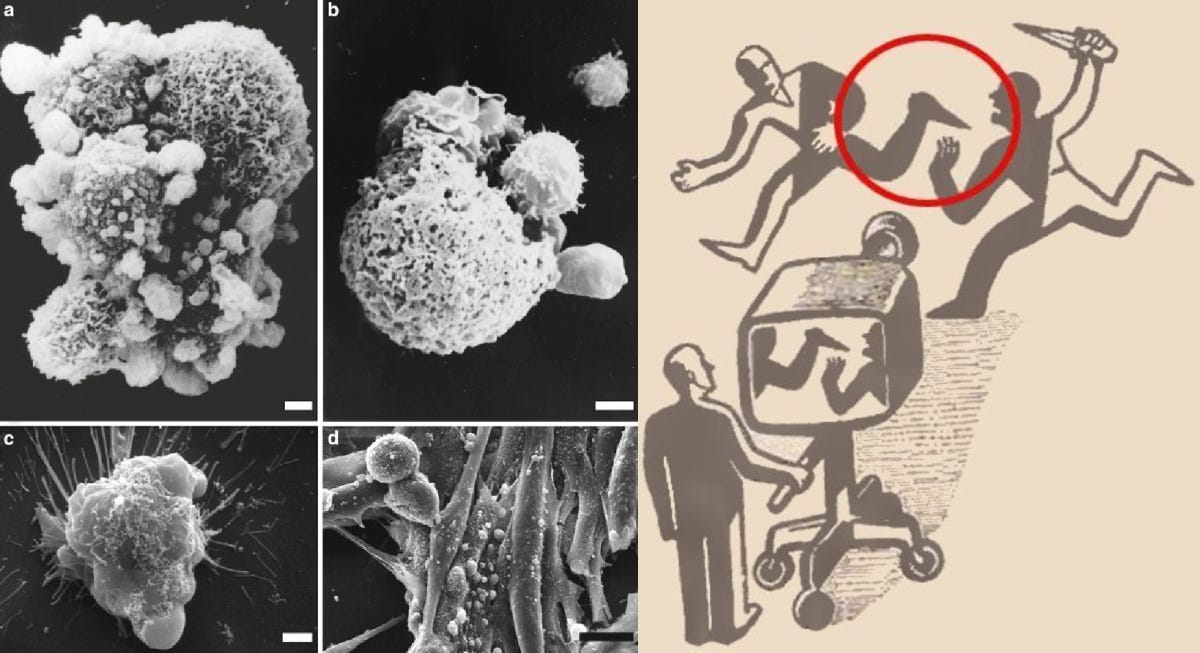

Consider a scientist examining diseased tissue under a microscope, observing either millions of bacteria or viruses surrounding diseased cells. This observation becomes problematic because:

Laboratory samples on Petri dishes, removed from the body's complete ecosystem, distort and eliminate interconnectivity. They obscure how other bodily processes influence outcomes.

Microscopic observations provide only snapshots without context—like entering a movie theater midway through a film, it takes a while to understand what’s going on.

Our educational system fails to teach the relativity of intellectual perception, how it functions, and how fundamentally it differs from nature's integrated consciousness.

These factors create a powerful illusion that microscopic organisms observed near diseased tissue must cause the disease. We rarely consider the reverse possibility—that the body might produce these microorganisms to consume decaying material and remove it.

The Vermin Sanctuary: Reconsidering the Ecological Model

Natural law suggests something entirely different: lacking consciousness, bacteria and viruses cannot know whether their existence benefits or harms the body. Concepts of "good" and "bad" emerge from cumulative process of an observer interpreting observed phenomena. From the body's perspective—which reflects nature's cognition—microscopic particles indicate processes occurring within the body and their purposes. Viruses, bacteria, and similar entities function more as "traces" for "trackers" to understand "what happened here."

A single bacterium divides every 20 minutes. Within 8 hours, this process yields millions of offspring; within 24 hours, over a billion. Theoretically, the descendants of just one bacterium could annihilate humanity. Yet despite breathing and swallowing thousands of microbes hourly, such catastrophic growth never materializes. Why? The answer is elegantly simple: without suitable nourishment (waste materials), bacteria cannot proliferate and eventually perish.

Consider this urban ecosystem analogy: imagine a city as a complete cosmos where daily human activities maintain a delicate balance through services, work, and infrastructure. What happens when garbage collection suddenly stops—perhaps due to strikes or equipment failure? Waste accumulates, rats proliferate, and crisis ensues.

Germ theory, however, inverts this causality. It suggests rats cause garbage rather than garbage attracting rats. The absurdity becomes apparent when framed this way, yet our medical paradigm follows precisely this flawed logic.

In other words, we’ve transformed bacteria/viruses from evidence into culprits. Microorganisms once understood as "traces" are now interpreted as "criminals." Disease sites become “crime scenes” where we frantically attempt to "apprehend perpetrators before they cause further destruction." Throughout this process, observers remain unaware of how they anthropomorphize microscopic entities, attributing them with human-like malicious intent.

This cognitive error forms the recipe for fundamental misconception. The fact that every epidemic throughout history—including COVID-19—ultimately concludes with reluctant admissions that "the virus spreads anyway" and "we must learn to live with it" hints at profound limitations in our model. But perhaps the most compelling evidence against contagion theory comes not from analogies but from controlled experiments conducted by germ theory's own advocates.

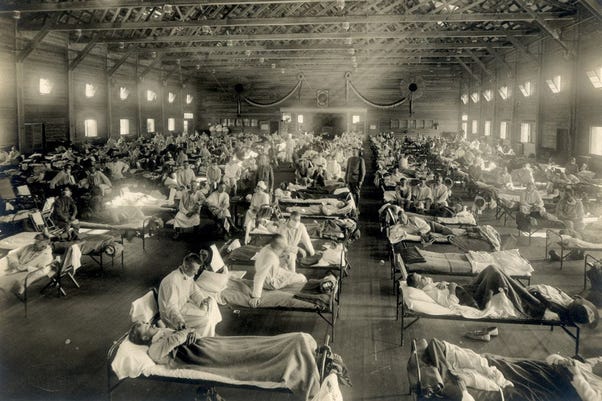

The Spanish Flu Experiments: When Contagion Theory Failed Its Own Test

Among the most revealing challenges to germ theory were experiments conducted during the 1918-1919 "Spanish Flu" pandemic—a disease that affected one-third of humanity and claimed approximately fifty million lives. This catastrophe provided the perfect laboratory for testing contagion models.

Dr. Milton J. Rosenau, a U.S. Public Health Service physician whose career thrived on germ-based fears, conducted controlled experiments on Gallops Island in Boston Harbor. His goal: demonstrate disease transmission from sick patients to healthy volunteers.

The results defied all expectations:

Researchers extracted mucus from infected patients' throats and even lung material from corpses, transferring these directly into volunteers' respiratory tracts. "We used billions of organisms," Rosenau reported, "but none of them became ill."

When they drew blood from sick patients and injected it into ten volunteers, "none became ill in any manner."

For their third experiment, researchers attempted to mimic "natural transmission": patients were instructed to exhale and cough directly onto volunteers who sat beside sickbeds, shook hands, and engaged in close conversation for five minutes.

In the most extreme attempt, patients forcefully exhaled directly into volunteers' mouths from just two centimeters away, with volunteers inhaling as patients exhaled. This process was repeated five times per volunteer.

Despite these extraordinary efforts, "none became ill in any manner." Similar experiments conducted throughout the pandemic yielded identical results. Rosenau, deeply committed to the germ theory paradigm, reluctantly concluded: "Perhaps there are factors in influenza transmission we don't recognize... Perhaps if we've learned anything, it's that we're not entirely sure what we know about this disease."

What makes this example particularly compelling is that it was conducted by a mainstream scientist fully devoted to germ theory, with results published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association. Yet despite clear evidence that the Spanish Flu didn't conform to contagion predictions, modern medicine continues to ignore these findings, clinging instead to a more convenient and profitable paradigm.

Science's Corruption: The Cost of Lost Sensory Wisdom and Spiritual Disconnection

Thousands of years ago, when our relative mental awareness was just emerging, humanity possessed an innate safeguard against dangerous misinterpretations of reality. We lacked understanding of the unity underlying apparent separation, yet we were equipped with an essential "insurance policy" protecting us from drawing destructive conclusions.

In a world divided into constantly shifting relative perspectives, we risked developing flawed conclusions leading to actions with catastrophic unintended consequences. Twenty thousand years ago, we couldn't comprehend the connection between hurricanes destroying our settlements and the slaughter of 100,000 bison in a single year. We didn't understand why incest created genetic dead ends—we hadn't even conceived the concept of "genes."

This safeguard was morality.

Morality—later formalized as scientific ethics—functioned as cognitive training wheels while our analytical abilities matured. It bridged the gap between our limited rational understanding and the vast unknown, fostering humility about what lay beyond immediate perception and the constraints of rudimentary language. Morality served as a cognitive bridge spanning the chasm between our immature rational knowledge and the unseen spiritual dimension (what we now might call "quantum physics"—the invisible fabric connecting all existence).

For millennia, humanity developed its mental consciousness primarily through deep sensory experience. Ancient educational systems invariably centered on practical application—archery training, glyph writing, craftsmanship requiring years of apprenticeship, agriculture—all fundamentally physical and sensory-based. Theoretical understanding complemented and emerged from direct physical experience.

For example, Hawaiian language contained dozens of terms distinguishing between subtle types of rainfall. Australian Aboriginals navigated vast distances by reading minute changes in wind patterns, stellar positions, animal behavior, and water sources' scents from miles away. Their “song lines” mapped an entire continent through sensory landmarks.

Traditional sailors predicted weather days ahead by interpreting wave patterns, cloud formations, wind shifts, and seabird behavior—knowledge transmitted through apprenticeship rather than texts. These examples demonstrate sensory wisdom cultivated across generations. A practical knowledge derived from intimate natural connection rather than theoretical models or technological instruments.

Approximately two centuries ago, human consciousness reached a critical inflection point. While we gained access to broader cognitive capabilities, we simultaneously began losing our sensory acuity and interconnected awareness—the intuitive perception that everything relates to everything else with no true separation. What we call "common sense"—intelligence derived from experience and deep sensory impressions—began fading. Human collectivization accelerated through mass migration, urban development, and unprecedented technological industrialization.

Consequently, we developed increasing technological dependence for information gathering and storage. On one hand this enabled us to amass profound knowledge that enabled profound progress. On the other, we generated endless theoretical models. Computers suddenly enabled infinite juxtaposition of isolated information fragments. As a result, humanity, and collective science in particular, began to progressively disconnect from nature.

Consider the contrast between a farmer's knowledge and a laboratory scientist's approach: The farmer holds no credentials and may speak awkwardly without sophisticated vocabulary. His clothes are soiled, his fingernails dirt-stained, yet within minutes he can assess his crops or livestock conditions through sensory information accumulated over years—reaching conclusions that would require a laboratory scientist, despite advanced tools and technology, weeks or months to determine.

This consciousness shift also marked the point where morality began dissolving, for in reality, the source of our morality was also the source of our sensory-based, tactile cognition. Our protective training wheels began to disappear, initiating science's gradual transformation from truth-seeking endeavor into a tool for social advancement and commercial profit.

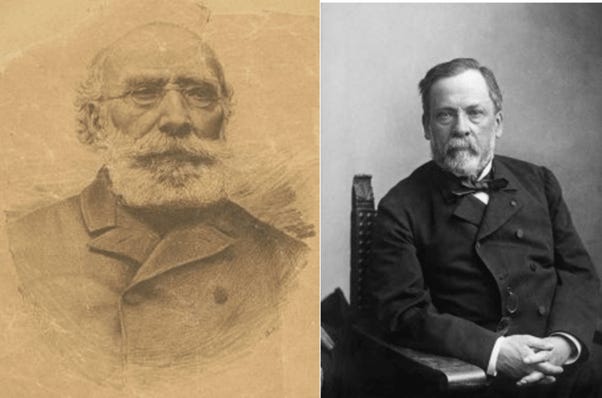

Louis Pasteur and the Transformation of Scientific Ethos

Louis Pasteur exemplifies the stark shift from truth-seeking science to influence-driven research that characterized 19th century France. Despite lacking formal medical or biological training, Pasteur's career trajectory reveals a man focused primarily on wealth and fame rather than genuine scientific inquiry.

Pasteur popularized the concept that diseases originate from specific external pathogens (germs) that attack the body. Through highly publicized theatrical experiments, including his famous French Alps expedition to collect air samples, he reinforced the perception that disease agents exist as discrete entities outside the body. For forty years, Pasteur conducted variations of the same experiment: identifying sick individuals, claiming to isolate bacteria, transferring supposedly pure cultures to animals (often through brain injections), and documenting their subsequent illness. This work led to pasteurization—a process that destroys milk's nutritional integrity and health-promoting properties.

His research approach consistently demonstrated opportunism, self-promotion, and strategic alliances with influential figures like Napoleon III. This formula transformed Pasteur into the celebrity scientist of his era, garnering royal honors and governmental accolades. Yet his private journals—which he explicitly instructed his family never to publish (a directive his grandson eventually violated)—reveal striking contradictions between his public claims and private practices. These journals contain Pasteur's unequivocal admission that he failed to transmit disease through pure bacterial cultures.

In reality, Pasteur only successfully transmitted disease either by introducing entire infected tissue samples to animals or by deliberately adding toxins to cultures—knowing these would induce symptoms in recipients1.

The Fundamental Template of Microscopic Life

While Pasteur advanced his reputation and germ theory, Antoine Béchamp—a skilled physician-scientist—was making revolutionary discoveries about "microzymas," microscopic entities he identified as life's most fundamental building blocks. Béchamp discovered that these microzymas constitute every cell and possess remarkable adaptive abilities, changing form (pleomorphism) in response to their environment.

The term "microzyma", derived from Greek "micro" (small) and "zyma" (suggesting activity, as in "enzyme"), reveal their essence. PThese tiny organisms' vigorous biological activity emphasize life's most fundamental generators.

Perhaps Béchamp's most astonishing finding was that microzymas could remain dormant (seemingly non-living) for thousands or even millions of years before "reawakening" under appropriate conditions. Experiments with ancient limestone and sedimentary rocks millions of years old—the byproduct of fossilized organisms—demonstrated that trapped microzymas retained life potential, capable of reactivating and initiating fermentation when placed in suitable environments.

This revolutionary discovery challenged the conventional living/non-living binary distinction, suggesting instead that life exists as a potential continuum that manifests or remains dormant according to environmental conditions. For Béchamp, microzymas represented not merely life's building blocks but also the connective thread between past, present, and future life forms—carriers of biological information capable of surviving beyond their host organisms.

Béchamp's work demonstrated that so-called “invading bacteria” might actually be microzymas that had transformed in response to environmental conditions. This inherently holistic approach centered on the body's internal environment ("terrain") rather than external pathogens, aligning more closely with nature's complex, interconnected systems.

Deceit in the Name of Fame and Opportunism

Despite rigorous scientific experimentation supporting Béchamp's theories, the scientific establishment rejected his work in favor of Pasteur's simplistic model—not because of superior scientific accuracy, but because germ theory better suited industrial commercialization, proved easier to understand and market, and offered clear-cut "solutions" (vaccines) with significant profit potential.

Béchamp, a principled scientist devoted to scientific truth, lacked the political patronage and institutional authority that Pasteur wielded so effectively. Rather than acknowledging Béchamp's significant contributions or engaging meaningfully with his ideas, Pasteur resorted to questionable tactics. His scientific practices frequently involved misrepresenting rivals' work, appropriating others' discoveries, and conducting what historian Geison characterized as "outright fraud" during his anthrax vaccination demonstrations.

Béchamp documented four specific instances where Pasteur plagiarized his work. In a disturbing irony Pasteur launched defamation campaigns against the very research he had stolen. This pattern exemplified what Béchamp termed the "conspiracy of silence"—a coordinated effort to suppress and erase his contributions from scientific history.

The ethical divide between these scientists extended to animal treatment. Pasteur's animal experiments were particularly disturbing, involving numerous cruel procedures on dogs, rabbits, and other mammals. He regularly performed trepanation—a horrific procedure where a living dog's skull was opened to examine its brain. He frequently injected one animal's crushed brain matter into another animal's brain to "demonstrate" infection transmission—practices so barbaric they became targets for 19th-century animal rights activists.

Pasteur's callousness toward suffering aligned with the spiritual perspective. This scientific approach, which disregarded suffering while elevating results above ethical means, contrasted sharply with Béchamp's methodology, which sought to minimize animal cruelty.

Significantly, since Pasteur's era, no researcher has experimentally demonstrated disease transmission through pure bacterial or viral cultures. Pasteur himself admitted this failure, leading to his famous deathbed confession: "The microbe is nothing; the terrain is everything"—referring to the organism's overall condition and internal environment.

Pasteur's conduct represented more than personal ethical failure—it reflected a profound consciousness shift that reflected in science increasingly serving industrial interests and academic prestige became linked to commercial potential. The coldly utilitarian approach embedded in modern science, where animal suffering became "necessary for progress," reflected the same mindset that prioritized profit over truth.

Pasteur's triumph over Béchamp symbolized more than a scientific victory—it established a precedent where political influence and marketing prowess could supersede scientific rigor. The Pasteur Institutes that proliferated throughout France and Europe not only commercialized his vaccines but created a business model that became the template for modern science—a paradigm where scientific truth subordinates to economic interests.

Thus, germ theory established its dominance not through scientific accuracy but through commercial applicability. For over a century, this theory has not merely dominated Western medicine but has fundamentally shaped our entire approach to health, disease, and nature itself.

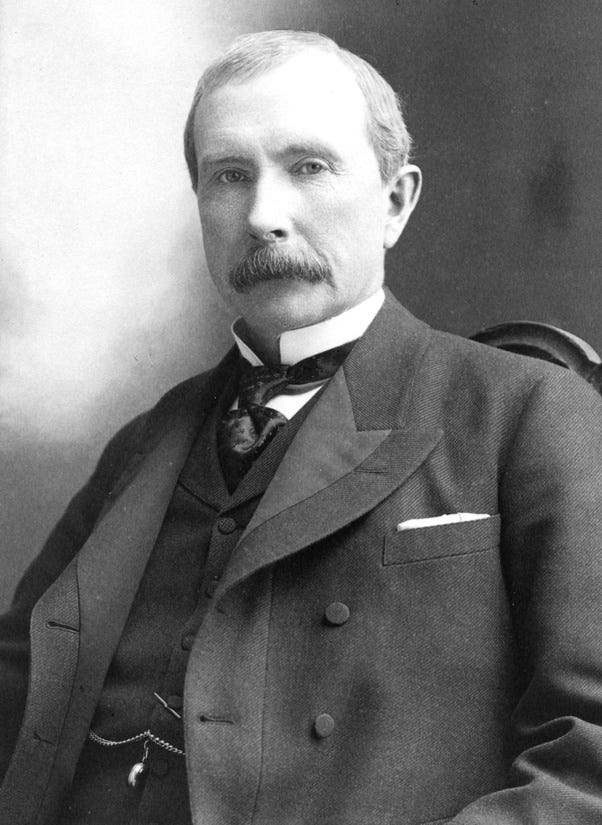

The American Evolution of Scientific Commercialization

To demonstrate that Pasteur's approach reflected a global shift in human consciousness, we need only examine how his French paradigm manifested in early 20th century America through the influential Flexner Report. While ostensibly reforming medical education, this 1910 document perfectly illustrates how scientific authority could be manufactured to serve industrial interests.

In the early 1900s, there were four main schools of medicine in the United States: allopathy (conventional medicine), homeopathy, naturopathy (then known as the eclectic school), and osteopathy. At that time, allopathy was at the bottom because its treatments were often ineffective and highly toxic.

In 1908, the American Medical Association’s newly formed Council on Medical Education wrote to industrialist millionaire Andrew Carnegie to propose a collaboration to “reform” medical education. The Carnegie Foundation was allied with the Rockefeller family, which had interests in oil and was now investing heavily in pharmaceutical companies. The group decided to hire Abraham Flexner to investigate medical schools in the United States and Canada. Flexner was a schoolmaster who knew nothing about the field of medicine.

The economic context proves crucial for understanding this transformation. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to dismantle the enormous monopolies created during the "Robber Baron" era. Magnates like John D. Rockefeller, who built the Standard Oil empire, needed new investment markets to preserve and expand their wealth.

Healthcare, with its enormous profit potential, presented an ideal opportunity. The Rockefellers established the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research and began acquiring pharmaceutical companies. Carnegie, having made his fortune in steel, created the Carnegie Foundation that funded Flexner's report. Thus, the very industrialists forced to dismantle their original monopolies effectively created a new monopoly over health through controlling medical education and defining "scientific medicine"—medicine requiring products their companies manufactured.

Given that Flexner's brother Simon directed the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, it's unsurprising that his findings heavily favored schools emphasizing pharmaceutical interventions. Wanting to improve the status of doctors, Flexner suggested closing most of the schools that allowed entry to women and black students. He advised the medical field to require specialization. And he insisted that funding and accreditation be given to only those medical schools that trained doctors in emergency and surgical medicine—both of which require the extensive use of drugs.

In response, the New York State Journal of Medicine recognized this power consolidation, "condemning the Carnegie Foundation for being dictatorial, for attempting to eliminate specific universities, for threatening the freedom of medical schools allowed to remain open, and for defaming anything that competed with the prevailing allopathic methods." However, most other medical organizations and publications praised the Carnegie Foundation’s goals precisely because of the clear bias against chiropractic, homeopathy, and all other forms of holistic medicine. The Journal of the American Medical Association supported Flexner’s position as truth.

Soon, the historic Flexner Report was widely acclaimed by everyone in the allopathic medical community. One hundred sixty medical schools had been open in 1905. But by 1927—just seventeen years after the Flexner Report was issued—that number dropped to eighty. That’s 50% reduction.

Thus, the Flexner Report completed what Pasteur began: transforming medicine from diverse healing traditions into a standardized industry serving chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturing interests.

World War II: The Acceleration of Synthetic Consciousness

While the Flexner Report laid the groundwork for medicine's industrialization, World War II marked a decisive turning point in humanity's relationship with health and the body. The war catalyzed an unprecedented shift toward synthetic solutions, as military research produced an explosion of chemicals, antibiotics, pesticides, and radiation technologies. This wasn't merely technological advancement—it represented a profound alteration in consciousness. The sterile, mechanistic approach to medicine found perfect resonance with the wartime mentality of control, standardization, and mass production.

Penicillin moved from laboratory curiosity to industrial production; DDT promised freedom from disease-carrying insects; and radiation technologies originally developed for warfare transformed into medical treatments. These developments weren't isolated from the Flexner paradigm but its logical extension—the final divorce of medicine from nature and its full embrace of synthetic interventions. This militarized approach to health, viewing the body as territory to be conquered rather than an ecosystem to be nurtured, became the dominant framework for post-war medicine.

From Wartime Innovation to Global Corporate Capture

This war-accelerated transformation of medicine created the perfect foundation for the next phase of health commodification. With synthetic approaches firmly established as the norm, pharmaceutical and chemical companies—many having profited enormously from wartime contracts—sought mechanisms to maintain and expand their influence during peacetime.

The stage was set for a profound global shift: the formal merging of scientific research with corporate profit through patent monopolization. This manifested first through the United States' Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, but quickly spread worldwide as a dominant model. In the decades that followed, a wave of similar legislation swept across both developed and developing nations. Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom implemented their own versions, as did China, Brazil, South Africa, and Malaysia. This was not coincidental but reflected a coordinated global restructuring of the relationship between public research and private profit.

These laws worldwide share the same fundamental mechanism: they allow institutions receiving government funding to patent and exclusively license discoveries made with public money. The Economist magazine called this approach "possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century," revealing how deeply this model aligned with commercial interests across national boundaries.

What began as the United States' Bayh-Dole Act became a global template, creating an international system where publicly funded research increasingly serves private profit motives. This worldwide shift established a perverse incentive structure ensuring that only research beneficial to pharmaceutical interests would receive funding. In this arrangement, citizens globally assume all research and development risks while private corporations extract the benefits—a perfect formula for creating pharmaceutical juggernauts while socializing costs and privatizing profits across national borders.

As revealed during the Covid pandemic, government health institutions worldwide no longer pursue scientific truth but function as sophisticated money-laundering operations—transferring public funds through agencies to research laboratories, which ultimately conduct research that is then licensed back to the benefactors, which are the pharmaceutical companies that helped place people in office in the first place.

The Germ Theory is convenient because it provides what every simplistic view of a problem seeks before all else: a culprit, an invisible hare for the hounds to chase in their costly research labs, universities, hospitals, and drug factories. The fact that the hare can never be caught is the perfect guarantee that their race will never finish, the demands for funding will never cease, and the ability to generate profits for the drug and chemical corporations will continue to grow.

Conclusion: Tracing Our Disconnection

What emerges from this historical exploration is not merely a critique of particular medical theories or institutions, but recognition of a profound pattern of disconnection. The mechanistic worldview that positioned germs as invaders to be conquered is the same mindset that fragmented our understanding of health, commercialized our fears, and systematically divorced us from natural processes. This disconnection serves specific economic and power interests while diminishing our collective vitality.

In other words, Germ Theory is an effect, not a cause. It reflects humanity's broader separation from nature and movement into a fragmented consciousness—one that fails to recognize connections between related phenomena, instead seeing each as isolated and independent.

This paradigm continues because it fits with and strengthens beliefs already deep in society, shaping how we all behave. It works in a circle: our fragmented thinking allows this science to exist, while this science makes our thinking even more fragmented. The result is the broken consciousness we live in today—a mindset that sees disease, health, and the body as battlegrounds rather than parts of a living whole.

This misattribution not only allows us to avoid personal responsibility but perpetuates these false patterns, enabling them to continue unchecked and unchallenged. Our reluctance to critically examine these inherited beliefs ensures we remain trapped in cycles of our own unconscious undoing.

In recognizing this pattern, we take the first step toward reclaiming both our health autonomy and our connection to the living systems that sustain us. When we shed unsubstantiated fears and reclaim our personal agency, we address the very disconnection that lies at the root of disease itself. This recognition isn't merely intellectual, it's the beginning of a fundamental healing that extends from consciousness to body, from individual to society.

In our next exploration, we will examine the devastating outcomes that emerge from clinging to the Germ Theory paradigm. We'll uncover how this flawed foundation has created cascading horrendous consequences throughout healthcare, social organization, and even our psychological well-being—effects that remain largely invisible until we step outside the paradigm itself. Join me as we continue to unravel the threads of this pervasive yet fundamentally flawed understanding of disease.

Source: Gerald L. Geison, "The Private Science of Louis Pasteur" (Princeton University Press, 2014).